Denmark – a nation protecting all its citizens

Denmark is the country which is a bridge between continental Europe and Scandinavia.

At the outbreak of World War II was a small island state with 4 million inhabitants living from agriculture, industry, fisheries and shipping. A homogenous population, Danish-speaking and Lutheran, with only small ethnic and religious minorities. A country that had taken in many immigrants from Germany, Holland, Sweden and Poland over centuries, quickly integrating them into the majority society.

In April 1940 Germany attacked Denmark despite the 1939 non-aggression pact that had been signed at the initiative of the Germans. The attack was part of an operation to occupy Norway.

The Danish government decided that Denmark could only be defended by way of diplomacy, not by military means. Therefore, the Danish military effort was limited and defensive, designed merely for a position of neutrality. So fighting was quickly over and a compromise reached.

The Danish government decided that Denmark could only be defended by way of diplomacy, not by military means. Therefore, the Danish military effort was limited and defensive, designed merely for a position of neutrality. So fighting was quickly over and a compromise reached.

The Germans granted Denmark certain “guarantees” at the outset: they did not come with hostile intent and would abstain from intervening in Danish domestic affairs, they said. Since Denmark was not formally at war with Germany, the government saw an opportunity to retain at least a part of Danish autonomy and national sovereignty.

So the political system continued to function. Its objective was to avert any warfare on Danish soil, limit the extent of German influence and block the Danish Nazis from rallying support.

The Danish king - in spite of the occupation- continued his morning rides on horseback through the capital with only two plain clothes police escorts following him on bicycles. He became a symbol for rich and poor alike, a positive contrast to German militarism and to the cult of the Führer. The king had only symbolic power in a constitutional monarchy such as Denmark, but the democratic government unanimously protected the Jews.

Denmark’s situation under the ‘peaceful occupation’ was calm and German policy very moderate. In Berlin, Denmark was referred to as a ‘model protectorate’. The British contemptuously called Denmark ‘Hitler’s parakeet’, although they showed understanding for Denmark’s difficult position at Nazi Germany’s doorstep.

Denmark’s situation under the ‘peaceful occupation’ was calm and German policy very moderate. In Berlin, Denmark was referred to as a ‘model protectorate’. The British contemptuously called Denmark ‘Hitler’s parakeet’, although they showed understanding for Denmark’s difficult position at Nazi Germany’s doorstep.

Germany’s moderate occupation policy had pragmatic as well as ideological reasons. Germany did not rob Denmark, but took out considerable amounts of supplies -- without actually having to pay, since the Danish National Bank offered credits that were unlikely to be paid. Equally important was the fact that the Danes were considered ‘Germanic’, ‘Aryan’ -- in other words ‘of good race’. In the long run, the Germans considered that the Danes would form part of the German people, and the Danish territory would become part of the German Empire.

In the autumn of 1941 the Germans pressured Denmark to join the Axis powers’ “Anti-Comintern Pact”. A year later, the Danish king’s chilly reply to a birthday greeting from Hitler unleashed a serious crisis, accompanied by German demands to appoint pro-German ministers.

General Hermann von Hanneken was sent to Denmark as new Commander-in-Chief of the Wehrmacht, and SS General Werner Best was appointed the German Reich’s Plenipotentiary and head of the German civilian administration.

Hanneken and Best were meant to tighten German rule in Denmark, but Best opted for continued cooperation with the Danish government and business community. In fact, in 1943 he even allowed parliamentary and local elections to be held.

Hanneken and Best were meant to tighten German rule in Denmark, but Best opted for continued cooperation with the Danish government and business community. In fact, in 1943 he even allowed parliamentary and local elections to be held.

The Final Solution

From the advent of Adolf Hitler’s dictatorship in 1933, Germany’s prime objective was to expand its imperial ‘Lebensraum’ and carry out an ‘ethnic cleansing’ of Europe. The National Socialist ideology was based on crude Social-Darwinism: human beings were seen as fundamentally unequal, some peoples and races as more valuable than others; those who were bestsuited should survive. Others would have to subject themselves to the rulership of the ‘master race’ or perish. According toNazi ideology, the Germans were chosen to be ‘rulers’. National Socialism was a racist ideology, and anti-Semitic in its core. Anti-Jewish sentiment was one of the most recurring elements in Nazi politics. Jews were assigned the role of the ultimate evil in the Nazi world view. They were referred to as parasites, vermin and disease, and were deprived of all human traits and rights.

One of the most important objectives for the Nazis was to marginalize the Jews from the rest of society. As soon as they came to power they began doing so. From 1933 on, the encroachments against the German Jews worsened step by step, leaving them isolated and robbed of all means of existence. Two thirds of the 500,000 Jews living in Germany (including Austria) felt forced to flee.

After the attack on Poland in September 1939 and the ensuing war of expansion, Germany had assumed control of the majority of Europe’s 10 million Jews.

These Jews were now subjected to ruthless oppression and discrimination, confined to ghettos and conscripted to forced labour. The Holocaust was launched in 1941, aiming at the systematic annihilation of all Jews. Even without a previous master plan, the genocide was carried out with cold-blooded, calculating efficiency.

The Jews during the occupation

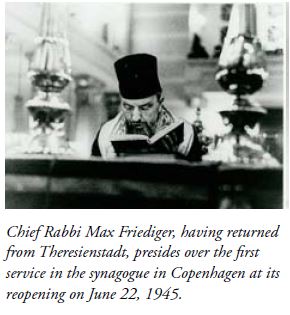

Meanwhile in Denmark there was a rumour started that Christian X had countered German demands for anti-Jewish legislation by threatening to wear the ‘Star of David’ in protest. The king in fact never did such a thing, but in December 1941, after an arson attack on the synagogue in Copenhagen, he did send a letter of sympathy to Rabbi Marcus Melchior.

The Jews were not registered, nor forced to wear the yellow star, because the Germans never brought forward the proposal, knowing that the government would turn it down. “There is no Jewish question in Denmark”, were the words of Foreign Minister, Erik Scavenius, when approached by the top Nazi Hermann Göring in Autumn 1941. Scavenius was willing to make far-reaching concessions to the Germans, but even for him, three issues were out of the question: the death penalty, Danish participation on the German side of the war, and racial laws.

The German occupation put Danish Jewry under enormous strain. The persecution of Jews in Germany was well-known via newspapers and personal acquaintances.

Even though the Danish government proclaimed that it would oppose all racial legislation and discriminatory measures, would it be able to withstand intensified German pressure?

The synagogue, Jewish schools and other institutions were discreetly put under the surveillance of young Jews and hooked up to the Danish police alarm system. The Jews were advised to avoid public exposure and direct contact with Germans. They tried to live as normally as possible but were constantly on the alert.

1943: the change of tides

Stalingrad, El Alamein, the landing of Allied troops in Italy, and major bombardments of German cities like Hamburg-- all of these events helped to produce a change in the Danish stance from compliance to defiance. The resistance got off the ground. Illegal publications and newsletters were circulated in ever larger numbers. German military targets and businesses working for the occupying power were increasingly subjected to sabotage actions as resistance fighters became more experienced and daring, and received air-dropped explosives and training instructors from Britain.

By July/August 1943, the Wehrmacht feared an Allied invasion on the Jutland coast. Danes sensed the panic and fostered the hope that a German defeat was impending.

‘The August Uprising’

A wave of sabotage actions hit the country in the summer of 1943. Unrest at Danish factories and shipyards is on the increase: social and political demands are voiced, authorities and organizations are meeting open criticism for their cooperation with the Germans. The unrest culminates in massive strikes supported by vast gatherings in many cities.

The occupying power sensed the gravity of the situation, and reacted sharply in some places, flexibly in others. The uprising continued however for most of August. Many Danes wanted to end what they saw as collaboration with the Nazis.

The occupying power sensed the gravity of the situation, and reacted sharply in some places, flexibly in others. The uprising continued however for most of August. Many Danes wanted to end what they saw as collaboration with the Nazis.

On August 29, 1943 the Germans declared a military state of emergency with authority handed over to the Wehrmacht Commander-in-Chief who hoped to edge out Best. Best is called to the Führer’s headquarters and reprimanded for yielding too much to the Danes. Two days later, however, Hitler returns the ultimate political responsibility to Best. He directs his energies at assuming dictatorial power in Denmark and requests that Berlin send police battalions to support it. He now intends to govern Denmark “with an iron fist”.

German action against the Jews

The systematic genocide of the Jews had been going on since 1941 at astonishing pace. By August 1943, 3 million Jews had already died in massacres or extermination camps. Earlier German advances at raising ‘the Jewish question’ in Denmark had been weak, though, mainly aimed at pacifying racial activists in Berlin. A small Jewish population like the Danish one (some 7,000) could wait, but now the time had come.

As the Danish government ceased to function on August 29, 1943, and the Danes announced that no new government would be formed, the cooperation policy between Denmark and Germany seemed to have collapsed. Best had used the strategy of punishing the Jews for resistance in the majority population earlier when he was stationed in France, and now the state of emergency proved to be an opportune time for anti-Jewish action in Denmark: protests could be easily suppressed, and Best could blame the Wehrmacht and thus keep the door ajar for resuming cooperation of some sort with the Danes in the future.

“The time has come”

On September 8th, Best sent a telegram to Berlin: hitting hard at the Jews is part of his new ‘strong hand’ policy, so “it is my opinion that if this new course of action is to be carried out fully in Denmark, the time has come to turn our attention to the solution of the Jewish question.”

One week later Hitler approved the deportation of the Danish Jews. Plans were immediately undertaken. A German police battalion was set up under the leadership of SS-Lieutenant Colonel Rudolf Mildner, former Gestapo chief in Katowice, Poland, and leader of the political department at Auschwitz. Specialists from Adolf Eichmann’s department at the Reichssicherheitshauptamt arrived in Copenhagen. Special German police forces were called in from abroad. The Wehrmacht, however, promised only logistic support, and would have no direct part in the manhunt.

The actual commencement of the operation was postponed somewhat, probably because the Germans wanted to end ongoing trade negotiations on next year’s Danish supplies to the Reich first.

On the day the state of emergency was declared, hostages were interned, among them prominent Jews. Since the Danish authorities had not conducted any registration of the Jews, the Germans and their Danish collaborators raided the Danish Jewish Community offices for address lists. Panic and uncertainty spread among the Jews: was there an action impending? Many went underground, some fled to Sweden. Danish officials confronted the Germans with the rumours, which were immediately dismissed.

An anxious calm prevailed during the month of September, but on the 28th an unequivocal warning was issued. On this day, Werner Best received the final go-ahead from Berlin. He informed Duckwitz, a German secret agent with contacts among the Danish Social Democrats, that the operation was at hand, and Duckwitz conveyed the warning straight away. Leading Social Democrats immediately inform persons in the Jewish community. C.B. Henriques, Supreme Court attorney and head of the Danish Jewish Community, first responds with disbelief. For three years now, Danish legislation and cooperation policy has protected Danish Jewry, and it is hard to admit that the legalistic strategy has failed to avert the disaster.

Duckwitz

On the next morning the warning is conveyed further during the service in the synagogue and through informal Jewish networks. Others receive word through gentile friends, business acquaintances or strangers wanting to help.

Here was something Eichmann and his men weren’t accustomed to: the Jews had slipped from their very grasp and disappeared, so to speak, behind a living wall raised by the Danish people in the space of one night.

On the night of October 1st/2nd, 1943, the German police operation begins. Throughout the country Jews are arrested. In Copenhagen, the synagogue is defiled and used as a pick-up spot. Despite the fact that it was Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) many Jews left their homes. A few hundred persons were arrested -- among them the elderly from the community’s old people’s home.

As a rule the Germans didn’t break into Jewish homes, since the action was supposed not to look like pillage. Most of the Jews have sought refuge at the homes of friends and acquaintances, or even complete strangers who spontaneously lend a hand. Others have fled to beach cottages and forests.

“On October 1st at 10 p.m. there was a sudden banging on my door. I had no choice but to open up. Before my eyes were two enormous German soldiers with guns at their sides, along with three civilians waving their revolvers at me. They commanded me to get dressed immediately, meanwhile ransacking all my drawers. Hardly five minutes had passed, then they commanded me to come along, at the same time mumbling almost confidentially that it was all right to bring cash and other valuables. The soldiers let me walk several steps ahead of them, and I have to admit I did consider whether there was any chance of escaping. But I didn’t dare take such a major risk. Finally they stopped in front of the gates of Forum, where a number of German officers were standing. One of them was particularly aggressive and gave me a couple of hard knocks on the head so that I fell to the ground, and I had barely got to my feet when another officer forced me up against the wall. Where I was standing was fully lit by floodlights, but it was still impossible to see the military person who gave the command “Anlegen!” I stood calmly and coolly, waiting to feel where the first bullets would hit me and hoping my life would end quickly, without prolonged agony. During those few seconds I thought about my family. Then suddenly I heard a new voice commanding me to get into a truck waiting nearby. I got to the truck, crawled up and remained there a while in total darkness. The door had been locked. Then it was opened, people got in, and the door was shut again. The truck was gradually filled in this manner, to the degree that we had to hunch together to make more room. Finally we were driven off to some place-- but where exactly, no one knew.”

A wall of people

It was widely felt among the Danes that the German action against the Jews transgressed all decency and violated Danish jurisprudence. No matter if you thought of Jews as aliens or ordinary Danes, you would have to help them in order to save your self-esteem. And 30-40,000 or more did so spontaneously by conveying warnings and organizing hiding places, food and transportation to the coast. In spite of the uncertain and trying, illegal conditions, rescue networks cropped up overnight, working with amazing efficiency.

The helpers represented all walks of life and diverse political beliefs, and they went to great lengths to help. The Danish police and coastguard also took sides with the oppressed by refusing to assist in the manhunt and informing helpers of the Germans’ movements. Even some individual Germans offered help, and at roadblocks Wehrmacht soldiers sometimes looked the other way -- moved by compassion or bribes.

Crossing the Øresund

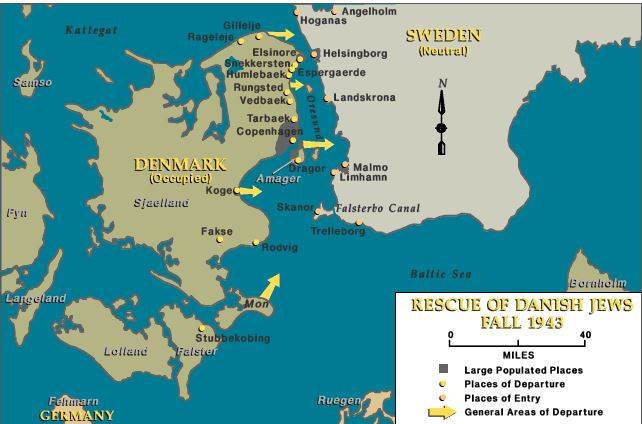

Geography was important. In some places, the Swedish coast was only 5-10 kilometers away. But getting across could be perilous; the Germans had only few patrol boats operational, but the crossing represented a risk factor, as did German airplanes.

Many fled in small craft or even kayaks at first. Tragic accidents were unavoidable in the leaky, over-filled dinghies that many inexperienced Jews set out in. Tragic deaths occurred when young, daring Jews attempted to swim across and got taken by the currents.

Many fled in small craft or even kayaks at first. Tragic accidents were unavoidable in the leaky, over-filled dinghies that many inexperienced Jews set out in. Tragic deaths occurred when young, daring Jews attempted to swim across and got taken by the currents.

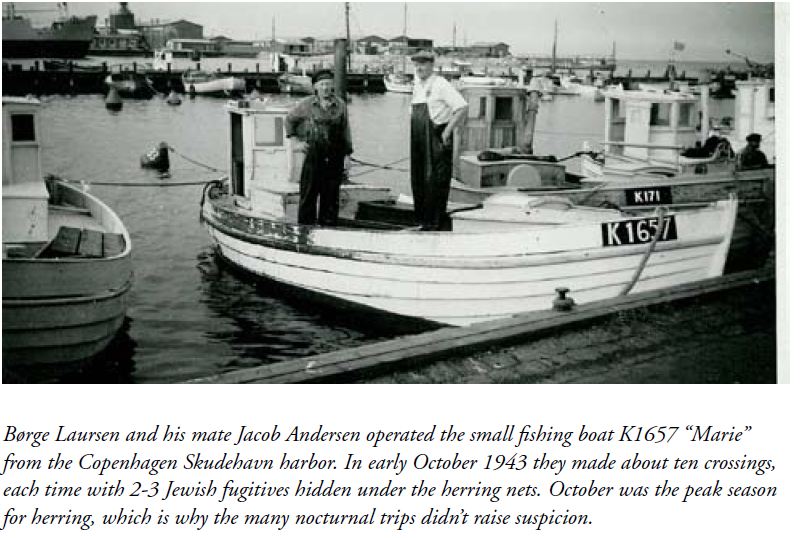

Fishermen played a vital part in the rescue operation. Even if the German coastal surveillance was not all that efficient, they knew that their boats, business and the livelihood of their families were at stake if they got caught smuggling Jews. Some operated for free, others demanded high prices for saving lives.

When rescue organizations intervened as intermediaries, prices were standardised and dropped. They also made provisions so that wealthy Jews would pay more, enabling those who couldn’t pay to get across as well. In today’s prices, the cost of an average crossing equalled 5-6 months wages for an unskilled worker, so substantial funding was needed. The money came from Danish organizations, companies and private individuals – and from the Jews themselves.

This original picture shows the fishing boat which took 15 Jews including 5 children on a ten hour trip from southern Denmark to Sweden, arriving only after daybreak in October 1943.

This original picture shows the fishing boat which took 15 Jews including 5 children on a ten hour trip from southern Denmark to Sweden, arriving only after daybreak in October 1943.

On October 10, 1943 medical officer H.G.Widding, who received refugees in Höganäs, Sweden, made the following note in his diary; his observation was typical for many Danish Jewish families because of widespread integration and assimilation:

On October 10, 1943 medical officer H.G.Widding, who received refugees in Höganäs, Sweden, made the following note in his diary; his observation was typical for many Danish Jewish families because of widespread integration and assimilation:

“Many of the children were frightened and couldn’t understand why they themselves had to flee. They were Danes and never gave it a thought that they were also Jews.”

Gilleleje, a medium-size fishing harbour, lies at the northernmost point of the island of Zealand with train connections to Copenhagen. About 20% of the Danish Jews escaped to Sweden via this town. Fishing boats as well as coastal freighters took part in the operation.

Jews were familiar with Gilleleje from countryside summer holidays and came to the area in droves. A committee of local people was quick to initiate rescue aid, even before representatives of Copenhagen-based rescue organizations arrived. Many helpers were needed to organize hiding places and food. In a small town like Gilleleje it was next to impossible to keep anything secret.

On the evening of October 5, 1943, a Gestapo search unit came to Gilleleje. A boat carrying fugitives had set out despite warnings and was stopped by German gunfire. Rescuers tried to round up and quickly hide new groups of refugees flocking to the town. Further sailing from the harbour was impossible, so the shipping-out of Jews was relocated to open beaches.

The following evening the Gestapo returned with reinforcements. They found a large group of fugitives hiding in the parish hall. The church was surrounded with floodlights and machine guns. Yet another group was hidden in the church attic. That night the Germans arrested 80 Jews, the majority of whom were deported to Theresienstadt. One young Jew escaped by climbing the clock tower and hiding there.

The Gestapo, unfamiliar with the area, demanded that the Danish police assist in the raid, but the Danish police refused. A local informer, however,had led the Germans to the church. Tragic as it was, this was the only case of a large number of Jews being caught during the clandestine rescue operation.

The Gestapo, unfamiliar with the area, demanded that the Danish police assist in the raid, but the Danish police refused. A local informer, however,had led the Germans to the church. Tragic as it was, this was the only case of a large number of Jews being caught during the clandestine rescue operation.

In an illegal sealift named “Small Dunkirk” by the resistance fighters, seven thousand people were conveyed by fishing boats and other small craft in the course of just a few days. Nothing had been planned in advance, so improvisational talent and courage were vital keys to success.

The contacts and experience that the rescue operation provided benefited the resistance in the long run. A whole network of illegal service routes was developed. One of these - the Danish-Swedish Refugee Service - was established by Zionist activists in Sweden. Some Danes proceeded from helping Jews to joining the resistance movement which also had a much easier time collecting money for its activities after October 1943.

Following the operation against the Jews, the state of emergency was called off. Without the reconvening of Parliament or the forming of a new government, the Danish administration, agriculture and industry still cooperated with the Germans, only more reluctantly. A kind of dual power situation prevailed, as the Danish population distanced themselves from the ‘old politicians’ who had engaged in the collaboration and increasingly looked to the Danish Freedom Council (an umbrella body of all left- and right-wing resistance organizations).

The Jewish deportees

The German police succeeded in catching only a small part of the Jewish population. Wartheland, the steamship that was to sail the arrestees to Germany, left harbour as planned from Copenhagen October 2nd with only 202 Jews aboard. 150 Danish Communists were deported along with them. A special train carrying Jews from the western parts of Denmark also ran more than half-empty. During the ensuing weeks the Gestapo made more arrests, but the total number of deported did not reach 500, whereas over 7,000 Jews managed to escape and reach Swedish harbours. Adolf Eichmann and his deputy Rolf Günter, who lead the operation in Copenhagen, had both suffered a defeat. Werner Best’s ambivalent policy had played into the hands of the Danish rescue activists. He tried to give the poor result the impression of a victory, proclaiming: “Denmark has been cleansed of the Jews”. At least, the Jews had been expelled from German-controlled territory. His superiors in Berlin were more than sceptical, though.

The Jewish deportees from Denmark were taken to Theresienstadt between Dresden and Prague. Here were tens of thousands of Jews crammed together in an old fortified city that served as a special ghetto. Of all the Danish Jews, these were the only ones who were forced to wear the Star of David.

Theresienstadt was the destination for Jews who were not intended for immediate annihilation. Conditions were not quite as extreme as in regular Nazi concentration camps, but the prisoners were starved, and suffered from deprivation.

Theresienstadt was the destination for Jews who were not intended for immediate annihilation. Conditions were not quite as extreme as in regular Nazi concentration camps, but the prisoners were starved, and suffered from deprivation.

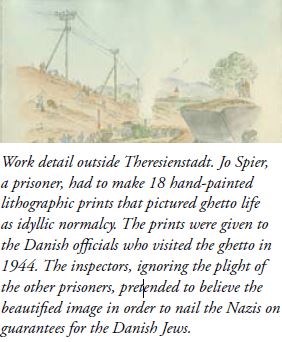

Frequent transports were dispatched to Auschwitz, where most Jews were killed immediately upon arrival. The Jews who had been deported from Denmark were, however, allowed to stay in the ghetto -- a promise the Danish authorities had obtained from Eichmann via Best. The Danes had no success in pushing for repatriation, but their wish to send inspectors to Theresienstadt was supported by Best who wanted to improve relations with the Danish authorities and business circles. Eichmann,for his part, was hoping to present to the world an idealized propaganda image and use Theresienstadt to conceal the fact of mass genocide, which by autumn 1943 had cost the lives of 3 million Jews.

On June 23, 1944 Danish officials inspected the ghetto and were presented with a heavily made-up stage set. The camp had been hastily remodelled, and thousands of prisoners had been sent off to Auschwitz.

Each of the prisoners who were chosen to speak with the inspectors were instructed about what to say, and knew that a false word would have grave consequences for themselves and their fellow prisoners.

Members of the commission represented the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Danish and International Red Cross. They obviously realized that they were implicated in a major Nazi charade, but hoped that by playing along they would be able to secure the Danish Jews at least minuscule protection. Soon, Denmark was also able to send food and medicine to Theresienstadt, and thanks to these supplies the Danish deportees experienced lower mortality than any other group in the ghetto.

Members of the commission represented the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Danish and International Red Cross. They obviously realized that they were implicated in a major Nazi charade, but hoped that by playing along they would be able to secure the Danish Jews at least minuscule protection. Soon, Denmark was also able to send food and medicine to Theresienstadt, and thanks to these supplies the Danish deportees experienced lower mortality than any other group in the ghetto.

The resistance had become ever more accurate in its attacks against pro-German businesses and attempted to block the transport of Wehrmacht troops by blowing up railway installations. The occupying power responded by issuing death sentences and sending many members of the resistance to German concentration camps. On September 19,1944 they even interned and deported the Danish police force.

Growing support for the freedom movement was countered by terror by the Germans and increasingly desperate Danish Nazi collaborators. A Danish newspaperman was murdered in retaliation for resistance actions.

The final battles of the war did not take place in Denmark. On May 5, 1945 the occupiers capitulated. Most of the Jewish deportees returned home.

A victory for civil resistance

The success of the rescue was due to several factors. The Jewish population was small and Sweden was close by, so the evacuation itself was a swift operation.

Moreover, the time that lapsed between the declaration of the state of emergency and the actual commencement of the German Aktion was long enough for the Jews to get organized and into hiding, not to mention the role of the warning that was given. But above all, it was due to local help: ordinary Danes were willing to take personal risks in order to help others in need. It was a widespread feeling in those days that any persecution of minorities was a breach of the values of democracy and Danish culture that had to be fended off.

The German authorities had never expected such a massive reaction – in most other countries, it had been easy to isolate and deport the Jews. But many Danes saw protecting Jews as a way of defending basic human standards, Danish sovereignty and self-esteem. And they were eager to deliver a blow to the occupying power before it was too late.